前回の港の歴史②では、

寺社が興隆し大きく反映した中世~近世の宇多津を振り返りました。

続いては、いよいよ宇多津の塩田の歴史を紐解いていきます。

In the previous article on the history of Utazu’s port (Part 2), we explored the town’s prosperity during the medieval to early modern period, when temples and shrines flourished. Now, we turn our attention to the history of salt fields in Utazu—a defining industry that shaped the town’s development.

「塩の街」宇多津、はじまりの時

畑さん

江戸時代末期になるとさらに海の方に街が広がり、

塩田業もスタートします。

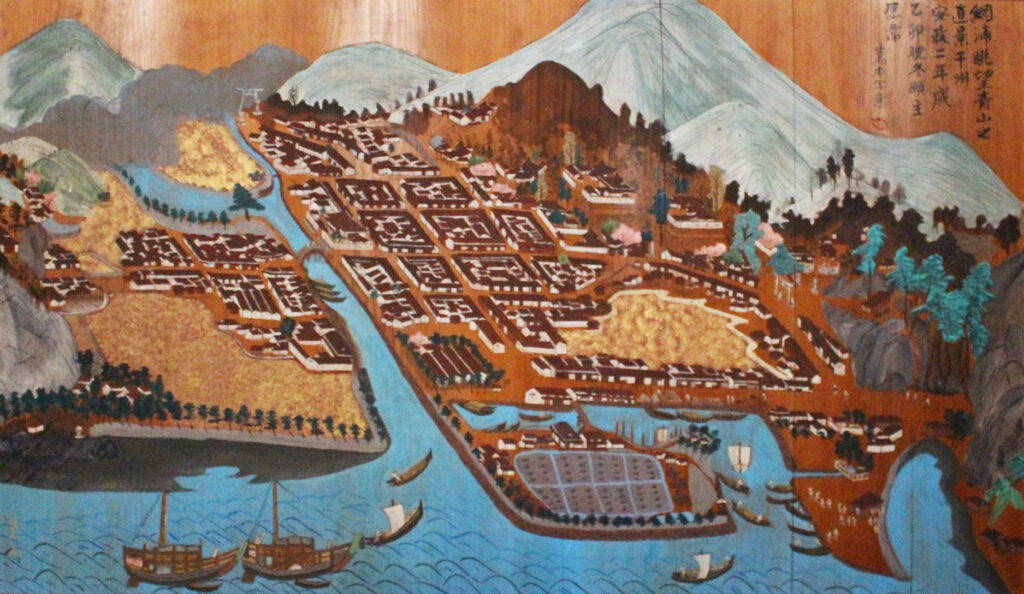

宇多津の宇夫階(うぶしな)神社境内にある金刀比羅宮に

1856年に奉納された絵馬には、

当時の街の様子が分かりやすく描かれています。

Utazu, the ‘Town of Salt’: The Beginning”

Hata-san:

“By the late Edo period, the town had expanded further toward the sea, and salt production had begun.”

An ema (votive painting) dedicated to Kotohira Shrine within the grounds of Ubushina Shrine in Utazu in 1856 provides a clear depiction of the town’s appearance at the time.

画面下は海なので北、上が南です。

右の方にある鳥居は宇夫階神社の鳥居でしょう。

“The bottom of the painting represents the sea, indicating that north is at the bottom and south is at the top.

The torii gate on the right is likely the torii of Ubushina Shrine.”

「網浦眺望青山真景図」(所蔵:宇夫階神社) Amiura Chōbō Seizan Shinkeizu (Owned by Ubushina Shrine)

その鳥居の前から、ゆるやかに曲がりつつ橋へと伸びる道が丸亀街道でしょう。

この橋は新町橋。今もありますね。川は大束(だいそく)川です。

玉井さん

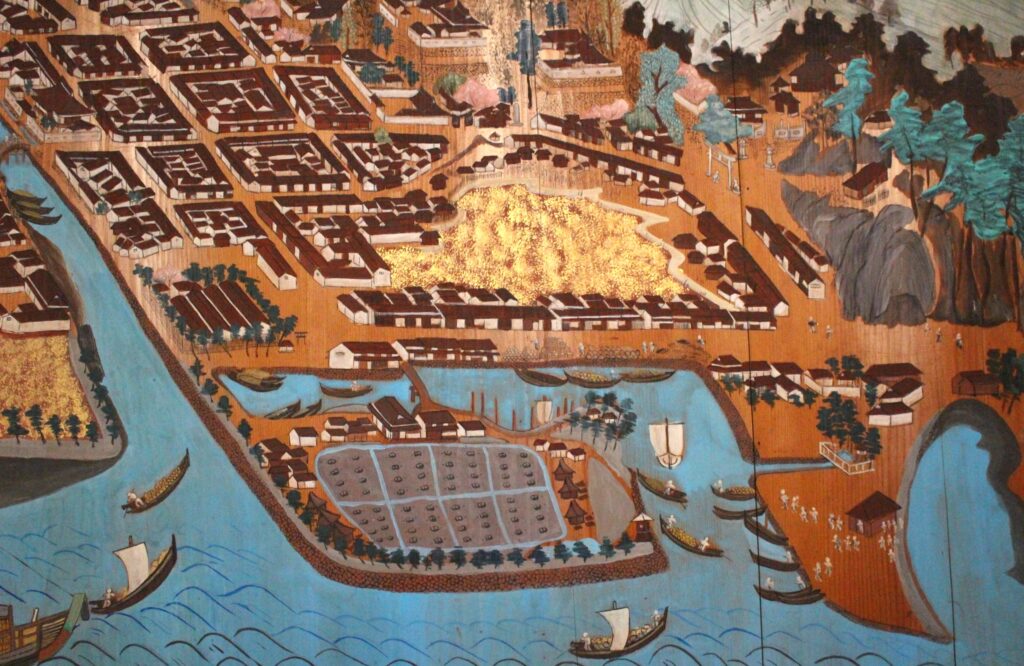

画面中央下に古浜(こはま)塩田がありますね。

古浜塩田の奥にある、薄金色の部分はなんでしょうか?

“The gently curving road extending from the torii toward the bridge is likely the Marugame Kaidō.

This bridge is Shinmachi Bridge, which still exists today. The river is the Daisoku River.”

Tamai-san:

“In the lower center of the painting, we can see the Kohama Salt Fields. What is the pale golden area beyond the Kohama Salt Fields?”

「網浦眺望青山真景図」(所蔵:宇夫階神社)(部分)

畑さん

今の幸町あたりですね。

これは泥、つまり干拓中なのだと思います。

護岸工事や干拓によって、宇多津の街は人工的に広がっていきました。

宇多津には今でも、当時の排水の水門や暗渠(あんきょ)などが残っています。

ちなみに塩田が完成したのは1745年。

なかなかの難工事だったようです。

「十州塩田」※の中では最も遅く、主要産地と比べても50~100年遅れてのスタートでした。

※近世~近代に瀬戸内沿岸の播磨(兵庫)、備前、備中、備後(岡山)、安芸(広島)、周防、長門(山口)、阿波(徳島)、讃岐(香川)、伊予(愛媛)の10ヵ国に存在した塩田の総称

古浜塩田は今でも海抜が低い地域です。

おそらくもともと土砂が堆積して「洲(す)」になっていたところを

さらに護岸してせき止め、塩田にしたのではないでしょうか。

Hata-san:

“This would be around present-day Saiwai-chō. That pale golden area is likely mud, meaning the land was still in the process of being reclaimed.”

“Through coastal protection work and land reclamation, the town of Utazu was artificially expanded. Even today, remnants of that era remain, such as old drainage sluices and underground waterways.”

“By the way, the salt fields were completed in 1745. It was quite a challenging construction project. Among the Jisshū Enden (Ten Provinces’ Salt Fields)*, it was the last to be developed, starting 50 to 100 years later than the major salt-producing regions.”

The Jisshū Enden refers to the salt fields that existed from the early modern to modern period along the Seto Inland Sea, spanning ten provinces: Harima (Hyōgo), Bizen, Bitchū, Bingo (Okayama), Aki (Hiroshima), Suō, Nagato (Yamaguchi), Awa (Tokushima), Sanuki (Kagawa), and Iyo (Ehime).

“Kohama Salt Field is still a low-lying area today. It was likely originally a sandbank (su), formed by accumulated sediment, which was then further reinforced with embankments and converted into a salt field.”

かつての自然港から人工港へと…

畑さん

江戸時代には港はだいぶ南下し、

古浜塩田の付近に移動しています。

西本さん

大型船は港内まで入れないので海側で待機し、

港へは小型船に乗り換えて移動していたと聞いています。

井村さん

大束川の河口付近、右側の茶色い屋根のかたまりが米蔵でしょうか?

「網浦眺望青山真景図」(所蔵:宇夫階神社)(部分)

畑さん

その通りです。

宇多津には1652年に高松藩の米蔵が置かれました。

今の町役場があるあたり、古街エリアの入口ですね。

玉井さん

現在の宇多津古街のまちの形は

この頃できあがったんですね。

背後に中世からのお寺がありながら、江戸初期からは蔵が整備され、

その後大束川の護岸が整備が完了したのは江戸中期頃。

かなり、時間がかかっていますね。

今、古街の街中は秋祭りやおひなさんといった行事の会場になっていて、

今、古街の街中は秋祭りやおひなさんといった行事の会場になっていて、

みなさんに歩かれ、親しまれていますが

江戸時代の人も同じ道を歩いていたのかな…と想像します。

畑さん

米蔵には藩の25%ほどの年貢米を保管していたので

容易に攻め込まれないよう、丁字路やクランクのような造りの道も多いですね。

だから今でも役場には真っすぐ行けない(笑)。

井村さん

港には大きな船が着けない、ということでしたが、

宇多津はあくまで米蔵のある街。

高松や上方(大阪)まで米や物資を運ぶ中継地であった、と考えることもできますよね。

西本さん

北前船の寄港地として栄えた近くの多度津(たどつ)とは、

港の目的が違っていたということですね。

玉井さん

丸亀藩との藩境ということもあって、

守りの要所として再整備されていったんですね。

From a Natural Harbor to an Artificial Port

Hata-san

During the Edo period, the port shifted significantly southward, relocating near the Kohama salt fields.

Nishimoto-san

I have heard that large ships could not enter the port and had to wait offshore, transferring cargo to smaller boats for transport to the port.

Imura-san

Could the cluster of brown-roofed buildings near the mouth of the Ōzuka River be rice warehouses?

“A View of Amiura and Its Verdant Mountains” (Collection of Ubu-kai Shrine) (Excerpt)

Hata-san

That is correct. In 1652, the Takamatsu domain established rice warehouses in Utazu. This area corresponds to the present-day town hall, located at the entrance to the historic district.

Tamai-san

So, the layout of Utazu’s historic district as we see it today was already taking shape at that time.

With medieval temples in the background, rice warehouses were built in the early Edo period. The embankment along the Ōzuka River was completed by the mid-Edo period—a process that took quite some time.

Today, the streets of the historic district serve as venues for events such as the autumn festival and the Hinamatsuri (Doll Festival). As people walk through these streets, I often wonder if those from the Edo period once walked the same paths.

Hata-san

Since these rice warehouses stored approximately 25% of the domain’s annual rice tax, measures were taken to prevent easy incursions. Many streets were designed with T-junctions or sharp bends. That is why, even today, you cannot reach the town hall in a straight line! (laughs)

Imura-san

It was mentioned that large ships could not dock at the port. However, Utazu itself was primarily a town with rice warehouses. It functioned as an intermediary hub for transporting rice and other goods to Takamatsu and Kamigata (Osaka).

Nishimoto-san

That means Utazu had a different role from Tadotsu, a nearby port town that prospered as a stop for Kitamaebune trading ships.

Tamai-san

Being situated on the border with the Marugame domain, Utazu was also fortified as a key defensive site.

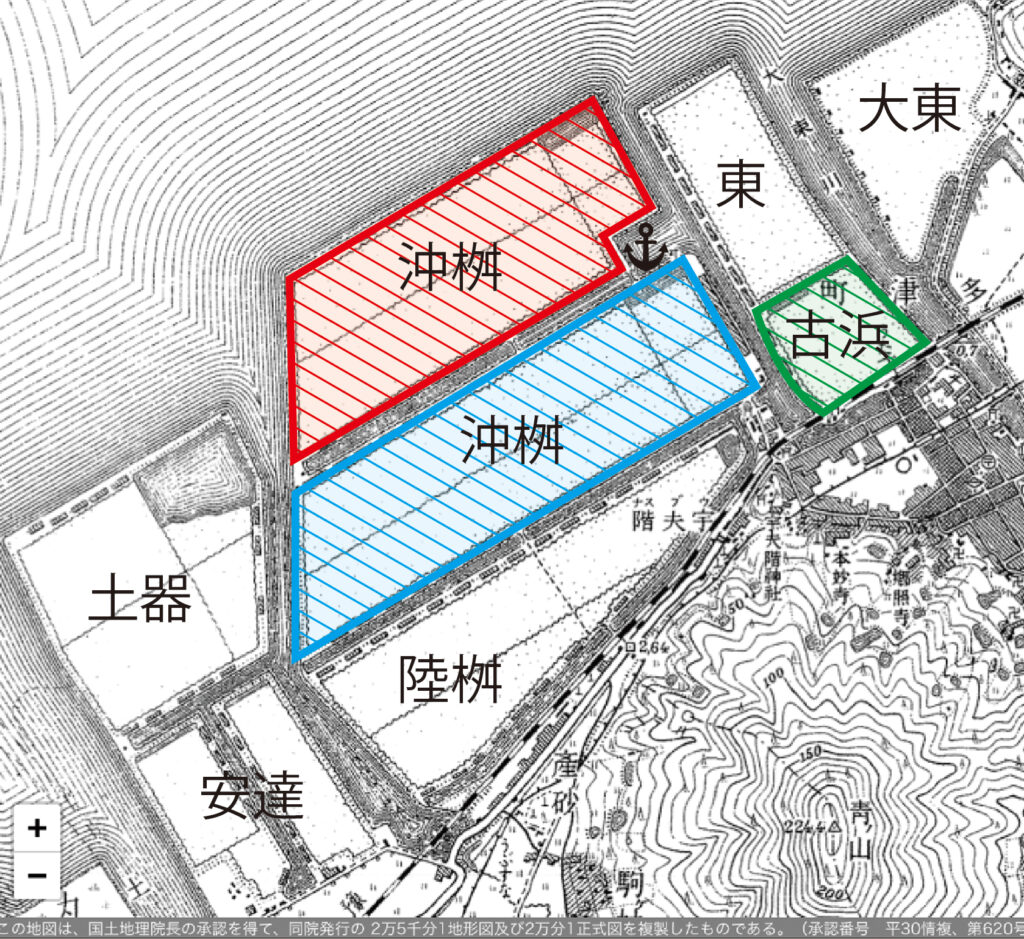

さらに広がる近代塩田

畑さん

明治に入るとさらに干拓が進み、

塩田は9haから203haへと拡張しました。

塩田時代の地図(国土地理院)より作成

しかし、これも時期としては少し遅かったんですね。

宇多津での供給最盛期には、国内全体としては塩は既に供給過剰になっていて

あまり高く売れなかったんです。

当時の最大生産量は年間7万t。

売上は70億円程度だったと考えられます。

塩田の面積を考えると…、ちょっとパフォーマンスは低いかな、という気がしますね。

横田さん

でも、「十州塩田」の中でも塩田経営を最後まで粘ったのは宇多津だったんですよね?

だからこそ、生産量日本一の時期もあったとか。

畑さん

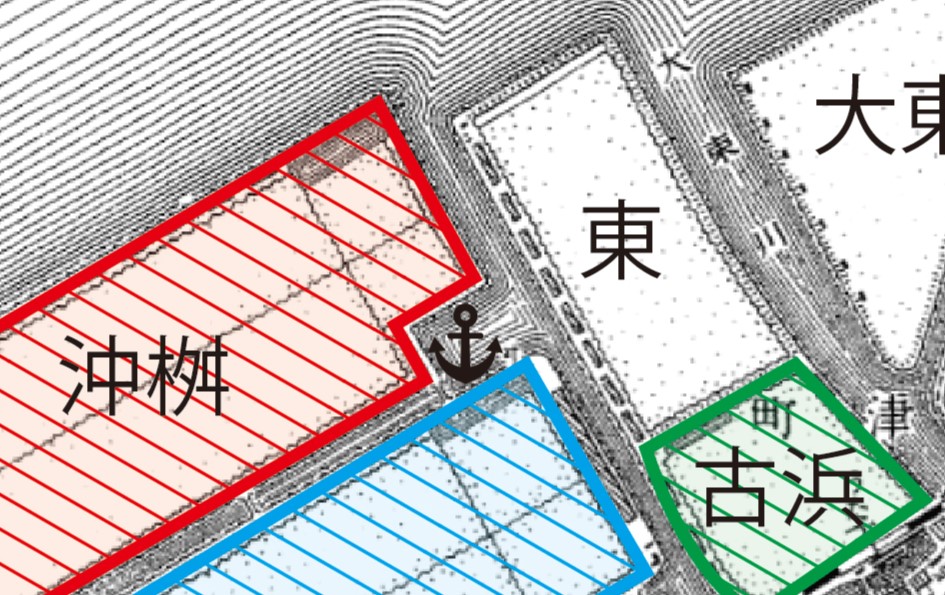

この頃の港の位置は…

みなさん、覚えていらっしゃいますか?

塩田の中で一番北側にある「沖枡(おきます)」塩田の南東の角あたりです。

私は子どもの頃に、聖通寺山から当時の宇多津を見下ろした絵を描いた記憶があります。

西本さん

昔の様子は、案外そういう子どもの絵に残っているのかも。

面白いですね。

The Expansion of Modern Salt Fields

Hata-san

With the advent of the Meiji era, land reclamation progressed further, expanding the salt fields from 9 hectares to 203 hectares.

(Map created based on historical maps from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan)

However, this development came somewhat late. By the time salt production in Utazu peaked, Japan as a whole was already experiencing a surplus in salt supply, meaning that prices were not very high.

At its peak, annual production reached 70,000 tons, with estimated revenues of approximately 7 billion yen. Given the size of the salt fields, the economic performance seems somewhat underwhelming.

Yokota-san

But among the “Jisshū Salt Fields,” Utazu was the last to persist in salt field management, wasn’t it? That’s why there was a time when it held the highest production volume in Japan.

Hata-san

Do you all remember where the port was located at that time?

It was near the southeastern corner of the Okimasu salt field, the northernmost section of the reclaimed salt fields.

I remember drawing a picture of Utazu as seen from Shōtsūji-yama when I was a child.

Nishimoto-san

Perhaps scenes from the past remain best preserved in children’s drawings. That’s an interesting thought.

塩田ついに廃止、「新都市」が誕生

畑さん

1971年に塩田が廃止となった後は、

半分にあたる約100aを「新都市」として一挙に開発することになりました。

引用元:Google社「Google マップ」を基に作成。

その後はみなさん知っているように、

大型商業施設やアミューズメント施設、そして集合住宅などが立ち並ぶ

現在の宇多津新都市の街並みができあがりました。

現在の港は旧沖枡塩田の北西の角。

商業港としての役割は終了し、

今では遊漁船の係留地となっています。

まとめ…宇多津は移り変わってきた街

大岩本さん

こうして聞いてみると、宇多津は本当に変化の大きい街なんですね。

玉井さん

古くから人が住み続けている土地でありながら、

時代によって海岸線と港の位置が変わり続けているというのが面白いです。

畑さん

環境の変化や土砂の堆積で、自然と海岸線が変化していた部分もあるし、

人工的に埋め立てて変化させていった部分もありますね。

また、時代に合わせて産業が移り変わってきたのも興味深いです。

古代には郡領地として、中世は交易の要、そして商業の中心地として。

江戸時代には高松藩の米蔵として。

その後徐々に塩田開発が始まり、最盛期を迎え、1972年に廃止されました。

現在では、その塩田の跡地が、中讃地域の商業的な拠点や住宅地─「新都市」として生まれかわりました。

江戸時代の趣を残す「古街」エリアも活用されています。

こうした宇多津の歴史の積み重なりを感じながら

街を歩いてみると、きっと色々な発見があると思いますよ。

本日はありがとうございました。

The Abolition of Salt Fields and the Birth of a “New City”

Hata-san

After the salt fields were abolished in 1971, approximately half of the reclaimed land, around 100 hectares, was rapidly developed into a “New City.”

(Source: Created based on Google Maps, provided by Google.)

As you all know, this area has since transformed into the present-day Utazu New City, lined with large commercial complexes, amusement facilities, and residential buildings.

The current port is located at the northwestern corner of the former Okimasu Salt Field. Its role as a commercial port has ended, and today, it serves as a mooring site for recreational fishing boats.

Conclusion: Utazu—A City in Transition

Ōiwamoto-san

Listening to this discussion, I realize how much Utazu has continuously changed over time.

Tamai-san

It is fascinating that, while Utazu has been inhabited for centuries, the coastline and port locations have shifted repeatedly throughout different historical periods.

Hata-san

Some of these changes occurred naturally due to environmental factors and sediment accumulation, while others resulted from deliberate land reclamation.

It is also intriguing to see how the region’s industries have evolved over time.

In ancient times, Utazu was a county administrative center. During the medieval period, it served as a hub for trade, and later became a commercial center. In the Edo period, it played a crucial role as the site of Takamatsu Domain’s rice warehouses.

From there, salt field development gradually began, reaching its peak before being abolished in 1972. Today, the reclaimed land has been transformed into a commercial and residential hub for the Chūsan region—the “New City.” Meanwhile, the “Historic District” still preserves the atmosphere of the Edo period and remains an active part of the town.

Walking through Utazu with an awareness of its layered history will surely lead to many new discoveries.

Thank you all for today.